hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

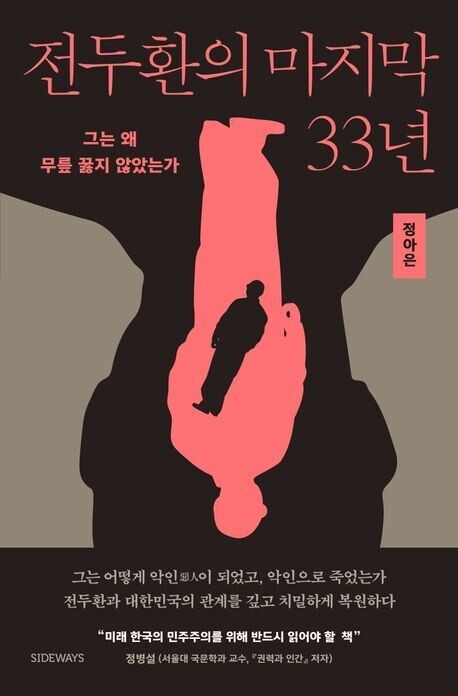

[Book review] Why the Butcher of Gwangju never apologized

By Jeong Ah-eun

Sideways

Not long ago, people were talking about the crisis of Korean cinema during the COVID-19 pandemic, but now the film “12.12: The Day” has become a box office sensation. Interestingly, the film has had an even bigger impact on younger viewers than on the middle-aged people who actually lived through the historical period depicted by the film.

In the publishing world, some of the books dealing with those historical events have also attracted readers’ notice. One of those is “The Last 33 Years of Chun Doo-hwan” by novelist Jeong Ah-eun. As the title suggests, the book doesn’t deal directly with the military coup that took place on Dec. 12, 1979. Rather, it focuses on Chun’s life from the end of his presidency in 1988 until his death in 2021. As a novelist, Jeong might have been expected to take a literary approach to the topic, but she opted for a nonfiction treatment.

After consolidating power by subduing an uprising in Gwangju with a bloody massacre in May 1980, Chun Doo-hwan spent a full eight years as president. Then he relinquished power to his colleague in the coup, Roh Tae-woo, and lived 33 more years as a “former president.”

During those years, Chun enjoyed the protection of a security detail in a “house” consisting of three buildings occupying 1,650 square meters and spanning four separate lots. He was occasionally invited to the Blue House to mingle with other former presidents and chat about the “future of the fatherland” and the “security of the state.”

As mentioned by “Chun Doo-gwang,” the film’s stand-in for the former president, Chun Doo-hwan was often accompanied to golf courses and fancy restaurants by close associates who had gotten their own sweet cut of his illicit deals.

In 1997, the Supreme Court upheld Chun’s conviction of accepting bribes under the Act on the Aggravated Punishment of Specific Economic Crimes and sentenced him to life in prison and a fine of 220.5 billion won. But since he succumbed to his chronic illness and died in 2021, at the age of 91, the 92.58 billion won that remained outstanding on his fine will never be collected.

Worst of all, Chun, a man who had committed such a monstrous crime before the bench of history, never said he was sorry.

The book was prompted by the simple question of why Chun never yielded. Jeong considers each aspect of Chun’s life the way a novelist might probe a character’s psychology and personal development. That process also sheds light on the nature of the era that he shared with us.

According to the author, Korea is the only one of several independent countries that emerged from World War II to become a member of the OECD, as well as the only foreign aid recipient to become a donor of foreign aid in the span of 50 years. Finally, the author observes, Korea is the only newly independent country that has accomplished the twin tasks of industrialization and democratization, forcing out no fewer than three leaders for corruption or illegal acts (Syngman Rhee, Chun Doo-hwan and Park Geun-hye) and replacing them with leaders elected by the people.

But Koreans have never properly punished the leaders they’ve chased out of office. How could that have happened?

There’s a simple answer. In the process of achieving modernity, Koreans have condoned expediency, extortion, falsehood, and the sacrifice of the weak and minorities, treating such things as inevitable aspects of the real world, all in the pursuit of achieving the impossible.

How was Chun Doo-hwan able to go 33 years without uttering a single word of apology, apparently feeling not the slightest bit of discomfort, not to mention any pangs of conscience, despite social pressure of all kinds?

Korea is the kind of place where a public prosecutor can rise to become a member of the National Assembly despite saying during a time of public outrage over a dictator’s crimes that a successful coup can’t be prosecuted. It’s the kind of place in which people who once prostrated themselves before Chun’s door are doing just fine today.

What the author found was not an answer, but another question: What is it about South Korea that prevented it from bringing to his knees a man who seized power illegally, killing and torturing so many people?

By Jeon Seong-won, chief editor of Hwanghae Review

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 11 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 4[Column] Can we finally put to bed the theory that Sewol ferry crashed into a submarine?

- 5[Editorial] Yoon cries wolf of political attacks amid criticism over Tokyo summit

- 6The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 7[Photo] “Comfort woman” survivor calls on president to fulfill promises

- 8[Editorial] Was justice served in acquittal of Samsung’s Lee Jae-yong?

- 9[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 10Doubts remain over whether Yoon will get his money out of trip to Japan