hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Fixation on trilateral military cooperation with US, Japan puts Korean peace last

Is all cooperation a good thing?

The dictionary defines “cooperation” as “joining forces to help one another.” In itself, there’s nothing bad about that at all. It’s certainly much better than dividing people or fighting among each other.

But the definition also does not consider the question of what these parties are joining forces and helping each other to do. They could be cooperating to beat up on someone powerless or to steal from others.

Mencius categorized the major virtues that human beings should observe into four types: benevolence, righteousness, propriety and wisdom. He also said the roots of these four virtues lay in the mind that feels compassion for others, the mind that despises evil, the mind that yields to others, and the mind that knows right from wrong. A central teaching of Confucianism is that we should cultivate our minds to practice these four virtues.

Laozi felt differently. “Do thieves also have ‘benevolence,’ ‘righteousness,’ ‘propriety,’ and ‘wisdom’?” he asked Robber Zhi, a famous thief at the time in ancient China.

Without hesitation, Robber Zhi replied, “Propriety is moving first before the others, righteousness is thinking of one’s own band, wisdom is knowing whether one has succeeded, and benevolence is when everyone fairly distributes what has been stolen.” In other words, even the best virtues are vain when one’s mind is focused on riches.

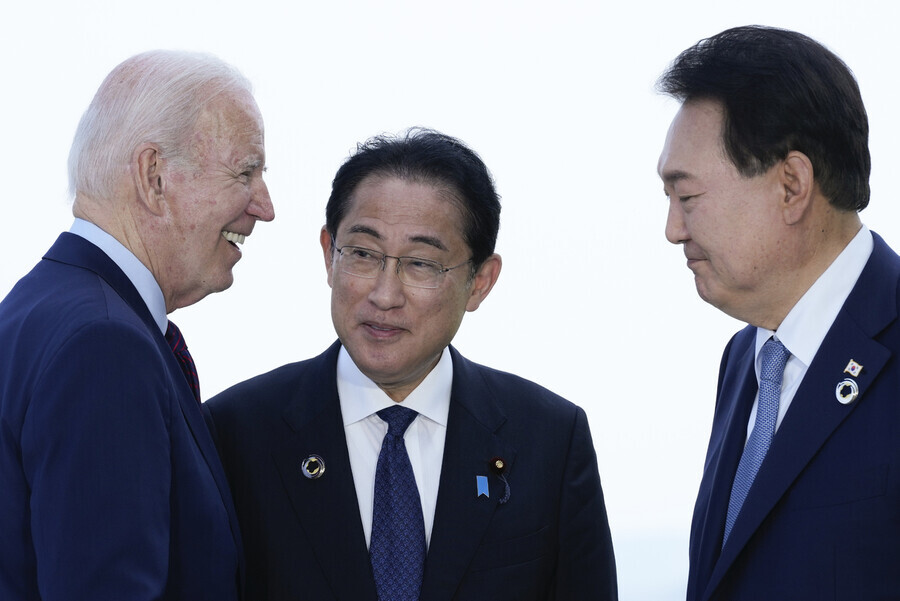

South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol, US President Joe Biden, and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida are suddenly putting great emphasis on “cooperation.” It is entirely to be expected that three countries would be joining forces to help each other — but what are they aiming to achieve with that? What agenda will be discussed at the trilateral summit scheduled to take place at Camp David on Friday, and what agreement will be reached?

Cooperation isn’t always a virtueThe White House has not spoken of a concrete agenda, saying only that there would be a great deal of things to discuss and that it looked forward to “historic” discussions.

But news outlets in Japan have been reporting that the dumping of contaminated water from Fukushima will be one of the subjects discussed at Camp David. According to them, Kishida is set to meet individually with Yoon and Biden to enlist their support for the water’s release into the ocean, citing a “scientific basis” for its decision.

It would scarcely be enough if the three leaders were cooperating to stop the pollution of international waters as a shared asset belonging to all humankind. But if they are joining forces specifically to contaminate the seas with radioactive substances, how are they any better than Robber Zhi?

It’s contradictory for them to talk about helping each other uphold “freedom of navigation” and a “rule-based international order” in the Indo-Pacific while contaminating the Pacific Ocean environment at the same time.

Moreover, freedom of navigation is an international law that applies to travels that cause no harm to other nations — yet the US Navy has been attaching “freedom of navigation” rhetoric to the military exercises it has been conducting right under China’s nose.

Whenever issues are raised with this, it insists on recognition of freedom of navigation as guaranteed by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which the US has not actually itself ratified. Its reason for not doing so is that it believes the passage permission system laid out in that convention could restrict its own warships’ and submarines’ freedom to travel all around the globe.

In their statement adopted in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, last November, the three leaders declared their resolve to “defend the rules-based international order.” But in the very same statement, they pledged to “work together to strengthen deterrence.”

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which bars all use, possession, production, testing, deployment, and transportation of nuclear weapons, was adopted by the UN in 2017. As of 2023, it has been ratified by 68 countries. It has entered into effect as the letter of international law.

But neither South Korea, the US nor Japan have yet to even sign it. Not only that, but they have declared on an international stage that they intend to cooperate to strengthen deterrence that centers on the use or threatened use of nuclear weapons. Can we call it “cooperation” when they are joining forces underneath the nuclear umbrella in the same global order where the TPNW operates?

In Phnom Penh, the scope of cooperation was confined to “shar[ing] DPRK missile warning data in real time.” But there are already signs suggesting that the discussions at Camp David will expand trilateral cooperation to the level of a quasi-military alliance.

We also see evidence that the US is moving to integrate the extended deterrence it individually provides to South Korea and Japan into a trilateral deterrence framework.

In early August, the Financial Times reported that the US hoped the summit would lead to South Korea and Japan “agree[ing] that each nation has a duty to consult the others in the event of an attack” against them.

Not only that, but there has also been speculation that the discussions will extend to cooperation measures related to trilateral military exercises, cyber security, missile defense, and economic security. When Biden shared a message in a speech last month welcoming South Korea and Japan’s cooperation and observing how they had “reconciled from World War II,” this was effectively a stepping stone toward a larger form of cooperation.

Saying no to cooperation aimed at conflictWhat would that cooperation be intended for? Some implications in that regard can be found in a report published by the US Center for Strategic and International Studies last January.

Titled “The First Battle of the Next War,” that report used a war game to predict what kind of battle would occur if China invaded Taiwan. Its conclusion was that China would suffer great losses and ultimately fail to occupy Taiwan, but that the US would also suffer enormous losses.

The basic war game presumed the US forces would be able to use military bases in Japan and that the Japan Self-Defense Forces would be joining the battle. While the scenario had two South Korea-based US Air Force squadrons taking part in the fighting in Taiwan, South Korea itself was not participating in combat.

The war game’s outcome was a situation of high losses suffered by the US and Japan. So what do the US and Japan hope to achieve through “cooperation” with South Korea?

The South Korea-US Mutual Defense Treaty is limited in scope to the scenario of “an armed attack in the Pacific area on either of the Parties.”

No legal basis exists for the Republic of Korea to be mobilized for combat in Taiwan, but summit statements have included an emphasis on cooperation for “regional security.” This is meant to leave open the possibility for Japan to intervene militarily on the Korean Peninsula, while also opening the door for “cooperation” where South Korea becomes involved in activities in the Indo-Pacific.

But there is another form of cooperation, one that the three leaders urgently need to pursue if they don’t want to follow Robber Zhi’s example.

With South and North Korea, the US, Japan and China all pursuing preemptive strike capabilities now, Northeast Asia is left in a precarious situation where one unfortunate incident could lead to war breaking out.

The taut tensions have also resulted in various incidents occurring. We saw one such dicey situation last month.

A B-52 strategic bomber from the US Air Force made an unexpected landing at Yokota Air Base, in Japan, at 10:22 am on July 12, apparently because of an equipment error that occurred during flight. That landing occurred only minutes after North Korea’s test launch of an ICBM. It’s unclear why this bomber (which is attached to the 5th Bomb Wing at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota) was flying at that precise place at that precise time or whether North Korea was aware of the B-52’s presence when it launched the missile.

Shouldn’t Korea, the US and Japan be cooperating not to present a threat or prepare to fight, but to reduce tensions and create an environment in which fighting is unnecessary?

By Suh Jae-jung, professor of political science and international relations at the International Christian University in Tokyo

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’ [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/5217153290112576.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’![[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/7717153284590168.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change- [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

Most viewed articles

- 1Korea likely to shave off 1 trillion won from Indonesia’s KF-21 contribution price tag

- 2Nuclear South Korea? The hidden implication of hints at US troop withdrawal

- 3[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- 4With Naver’s inside director at Line gone, buyout negotiations appear to be well underway

- 5In Yoon’s Korea, a government ‘of, by and for prosecutors,’ says civic group

- 6[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 7‘Free Palestine!’: Anti-war protest wave comes to Korean campuses

- 8How many more children like Hind Rajab must die by Israel’s hand?

- 9Overseeing ‘super-large’ rocket drill, Kim Jong-un calls for bolstered war deterrence

- 10[Photo] ‘End the genocide in Gaza’: Students in Korea join global anti-war protest wave